Desheret, or the Red Land, was the unforgiving desert beyond the cultivated soils, the place where the dead were buried. Western perceptions of Egypt have been built upon an Orientalizing notion of an antique, unchanging Egypt, a land obsessed with death. The reality, however, was a people striving to live, even beyond death. The ancient world had high mortality rates. Medicine and magic were equally valid ways of fighting disease, wild animals, and injury.

Desheret, or the Red Land, was the unforgiving desert beyond the cultivated soils, the place where the dead were buried. Western perceptions of Egypt have been built upon an Orientalizing notion of an antique, unchanging Egypt, a land obsessed with death. The reality, however, was a people striving to live, even beyond death. The ancient world had high mortality rates. Medicine and magic were equally valid ways of fighting disease, wild animals, and injury.

For those with means, death was a celebration of wealth. Bodies were adorned, burial objects were left with the deceased, and professionals were hired to bring water and food to the cemetery. The embalmers practiced their trade at Tebtunis, where they mummified humans alongside animals. Some of the crocodile mummies were placed within the inner temple as embodiments of the god Soknebtunis.

The mummies at Tebtunis had many stories to tell their excavators. Old documents and books were frequently discarded, but during the last three centuries BCE they were at times sold and reused to create cartonnage, a kind of papier-mâché. Animals and humans alike could end up wrapped in an account from an agricultural estate or even a Greek play. The written word became secondary to the material needs of the embalmers, who would mask the text with painted scenes of Graeco-Egyptian religion.

George A. Reisner (1867–1942)

Deir el-Ballas, Northern Cemetery

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, Reisner Manuscript #45

Embalmers and their Tools

Petition from an Ibis Embalmer (ibiotaphos)

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Mummy 16, Early Second Century BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. III 963

Petition from the Mummy Embalmers (taricheutai)

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Mummy 62, Late Second Century BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. III 967

Linen for the Burial of a Sacred Bull

Bilingual Greek-Egyptian receipt for a delivery of linen from Maron, a priest at Tebtunis

Tebtunis Town, T-148, 210/211 CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 313

Cartonnage from Human Mummies

Complete sarcophagi are often what draw the most attention in museums, owing to how elaborately decorated they were in ancient Egypt. The reality for most individuals was something more modest. During the Ptolemaic period, people were mummified, wrapped in linen, and then pieces of cartonnage, a kind of papier-mâché, were attached to the body. The mask was one of the most important objects added, not only because it protected the person’s head, but also because it provided an idealized, even godly, face for the deceased.

At Tebtunis and elsewhere, written texts often found their way into mummies, both human and animal. Papyrus could only be reused for writing so many times. Even rubbing off the ink and washing the surface left a stain. Once their front and back were full, papyri were often recycled; they could end up in mummies locally or traded to embalmers at a great distance. Several papyri would be layered, and a white plaster applied to conceal their original contents. Cartonnage was painted with protective funerary motifs and then attached to mummies.

Painted mummy mask with a gold face

Tebtunis or Akhmim, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20107

A fragment from a painted mummy mask made of papyri

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Unknown Mummy, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt.frag. 11,021

Pieces of painted cartonnage with image of four Sons of Horus

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Mummy 80, Mid-Second Century BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. III 771

Demotic papyrus reused to create a decorative panel for a mummy

Demotic papyrus reused to create a decorative panel for a mummy

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Unknown Mummy, Second or First Century BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt.frag. 10,751–10,756

Lower portion of a mummy’s wig decorated with two seated gods

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Mummy 83, Second Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. III 1087

Photograph of three mummy masks and other decorative elements (including P.Tebt.frag. 10,751–10,756)

Arthur Hunt (1871–1934)

Tebtunis, 1899–1900

Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society, GR.NEG.056

Faces of the Dead

Mummy portraits are paintings of individuals on wooden boards that were the face of mummies in the Roman period. The people depicted gaze at us from the past. These paintings on wood panels belonged to wealthy men and women, who paid artists to capture an idealized likeness, sometimes offering instructions (in Greek). Although found throughout Egypt, they were excavated in large numbers in the Graeco-Egyptian cemeteries of the Fayyūm. They were valued by early collectors for what they considered classical “realism” over traditional Egyptian style. We now know, however, that the people who look out at us were part of a complex multicultural society.

Mummy portrait with sketch and artist’s notes on reverse

Tebtunis Cemetery 7 or 8, Second Century CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21378a

Mummy Portrait of a Small Boy Holding a Pen Wrapped in a Scroll

Tebtunis Cemetery 7 or 8, ca. 110–140 CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21377

Mummy Portrait of a Jeweled Woman Wearing a Red Tunic

Tebtunis Cemetery 7 or 8, Mid-Second Century CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21376

Soknebtunis Manifest

Soknebtunis, the crocodile god of Tebtunis, had a temple with a long niche where a mummified crocodile could be placed. A mummy like this could be brought out on special occasions as a manifestation of the god. Although the skull of this crocodile is in place, a CT-scan showed that its body was stuffed with bones, reeds, and rope. The crocodiles were buried in a sacred cemetery near Tebtunis. Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt discovered that the embalmers reused papyrus in preparing these crocodiles much as they did with human mummies. For example, the archive of the scribe Menches was wrapped around these animals.

Mummified crocodile

Tebtunis, Third Century BCE to Third Century CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20100

Ornately wrapped votive crocodiles, of the sort sold to temple visitors leaving offerings to the god

Tebtunis Cemetery 6, Ptolemaic or Roman Period (Third Century BCE to Third Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21633

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21634

Photograph of various sized crocodile and cat mummies discovered at Tebtunis

Arthur Hunt (1871–1934)

Tebtunis, 1899–1900

Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society, GR.NEG.067

Images of crocodile mummies in their cemetery at Tebtunis

Gibert Bagnani (1900–1985)

Tebtunis, ca. 1934

Courtesy of the Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario. Gilbert and Stewart Bagnani fonds. Gift of Stewart Bagnani, 1991

Egyptian Literature and Science at Tebtunis

Papyrus describing the effects of the positions of the planets on a person’s fortune at birth

Tebtunis Town, T-19, Late Second Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 276

Text with an astrological treatise concerning the connection between the heavenly bodies and professions

Tebtunis Town, T-727, Third Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 277

Egyptian religious composition in demotic on the conflict between the sun god Re and his snake enemy Apophis

Egyptian religious composition in demotic on the conflict between the sun god Re and his snake enemy Apophis

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Unknown Mummy, Third Century BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt.frag. 14,433+14,434

Portion of a demotic text with the Inaros Epic, a cycle of Egyptian stories influenced by Homer

Tebtunis Town, T-228, First to Third Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt.suppl. 1,241

“If the god is angry with a house burn everything that is in it, because it reaches him.” So goes the advice provided in a piece of wisdom literature written in demotic Egyptian. At Tebtunis, the temple library would have contained copies of many such texts, although today only fragments have survived. This example contains of a commentary on a philosophical text. It has been suggested that this text bears thematic similarities to the Akousmata, or sayings of the philosopher Pythagoras. The composition highlights the intense exchange of ideas between Greek and Egyptian literature, philosophy, and science from the seventh century BCE onward.

Demotic wisdom literature with parallels in Greek philosophy

Tebtunis Town, T-228, Second Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt.suppl. 1,719–1,727

Mythology in Pieces

Mythology in Pieces

The Inachus, a satyr play (a type of tragic comedy) attributed to the fifth century BCE playwright Sophocles, is known from only two papyri, one of which you see here. Although details of the plot are unclear, it seems to revolve around the abduction of Io, daughter of Inachus, by Zeus. Other characters include a satyr chorus, many-eyed Argos, and the god Hermes. The few lines on this papyrus preserve a conversation between the chorus and Hermes before the killing of Argos.

Sophocles, Inachus (?)

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Mummy 15, Second Century BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. III 692

A Soldier’s Account of the Trojan War

The Diary (Ephemeris) claims to be a first-hand account of the Trojan War by Dictys, a soldier from the island of Crete. The prose narrative differs from the more famous poem by Homer in emphasizing the human aspect of the conflict. The popularity of the Ephemeris was unmatched through most of the Middle Ages and Renaissance owing to its Latin translation, but the text is poorly known today. In fact, many scholars doubted the existence of the work in Greek until this papyrus was identified as a fragment of that version.

[So], entering [the grove and] looking around the [who]le place they see [Achilles lying inside] the fenced area of the altar [covered with blood and still] breathing. To whom Ajax said, [“It was true then that none] else of mortals could [kill you since in warlike strength you surpass] all, but your own impetuousness [has destroyed (you).”

P.Tebt. II 268, col. 1, ll. 31-51

Translated by Donald Mastronarde

Dictys of Crete, Ephemeris (Book 4, 9–15)

Tebtunis Town, T-341, Early Third Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 268

Fighting off Death

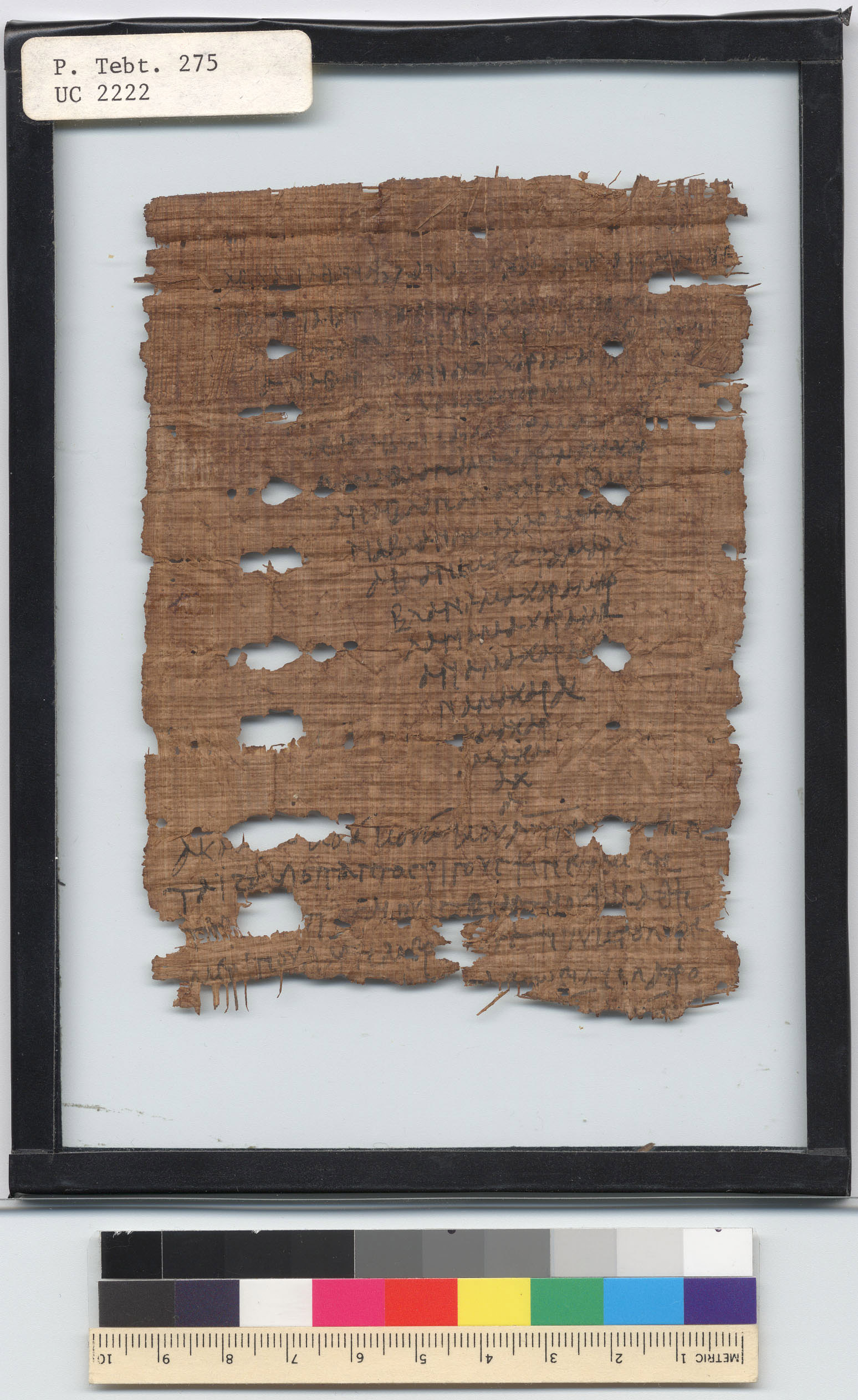

A magical amulet invoking a deity, Kok Kouk Koul, made for a woman. She would have folded it and worn it as part of a necklace around her neck to ward off malarial fever.

A magical amulet invoking a deity, Kok Kouk Koul, made for a woman. She would have folded it and worn it as part of a necklace around her neck to ward off malarial fever.

Tebtunis Town, Third Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 275

Egyptian Amulet

Deir el-Ballas, 18th or 19th Dynasty (1550–1186 BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-9619

Medical Treatment for Thirst Accompanying Fever

Herodotus (the physician), De Remediis

Tebtunis Town, T-423, Second Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 272

Death Notices

Village scribe is notified of the death of the priest Psoiphis

Tebtunis Town, T-14, 9 February 151 CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 300

Declaration of the death of one of the last priests of Tebtunis with a list of witnesses and the signature of the village scribe

Tebtunis Town, T-164, 27 November to 26 December 190 CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 301

Preparing for the Afterlife

This funerary stela belonged to a man named Peteminis. The deceased is depicted twice: On the top register he is shown lying as a mummy on a funerary boat below a winged sun disk and flanked by two jackals; on the central register, he is depicted in a scene surrounded by various gods. The god of embalming, Anubis, presents him before Osiris, the god of the dead and the ruler of the underworld. Isis, the wife of Osiris and a protective goddess, is also present and a table with different offerings is displayed for Osiris. The name of the deceased is written in Greek on the last register, where it is also mentioned that he died at age forty.

Limestone funerary monument with Egyptian religious motifs

Akhmim, Roman Period (First to Third Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-19921

Dress in Ancient Egypt

Clothing List from a Woman’s Dowry

Tebtunis Town, T-721, Third Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 405

Tunic with purple shoulder bands (clavi)

Tebtunis, Late Roman (Fourth to Sixth Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21373

Modern linen tunic with antique colored wool appliqués

Egypt, Islamic Period (Eighth Century CE Onward)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 5-16938

A Pot for Every Occasion

Pottery was the most commonly produced object in ancient Egypt. The ceramics found at Tebtunis come in a range of shapes and sizes—some locally made, some carrying imported goods from the far reaches of the Mediterranean. In death, pottery was deposited in the tomb with provisions for the afterlife. These complete vessels may have contained offerings of fruit, grain, or beer for the deceased.

Echinus-Style Bowl

Tebtunis, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20151

Achaemenid-Style Bowl

Tebtunis, Early Ptolemaic Period (Fourth to Third Century BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 6-20153

Straight-Necked Bottle

Tebtunis, Ptolemaic or Roman Period (Third Century BCE to Fourth Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 6-20154

Terracotta lamp decorated with a bearded face

Tebtunis, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20972

Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt used field notebooks to record observations and keep inventories of the objects that they had excavated and photographed. This page was devoted to numbering the pottery found at Tebtunis. Most of the pottery mentioned in the notebook of Arthur Hunt was sent to Cairo, but researchers have identified a number of pots in the collection at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Some of the pots at the PAHMA can be recognized from Hunt's photograph.

A page from the field notebook of Arthur S. Hunt (1871–1934)

1899–1900

Courtesy of the Griffith Institute Archive, University of Oxford, Crum MSS 24.67, pg. 15

Photograph of Ptolemaic and Roman pottery, some of which arrived in Berkeley in 1903

Arthur Hunt (1871–1934)

Tebtunis, 1899–1900

Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society, GR.NEG.062

Objects of Life Buried with the Dead

Blown glass oil or perfume bottle found in a burial

Tebtunis Cemetery 8, Roman Period (First to Fourth Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21428

Human figurine (ushabti) magically brought to life to work for the deceased in the underworld

Tebtunis Cemetery 5, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21140

A bronze open-circle bracelet with overlapping ends

Tebtunis Cemetery 5, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21368