Kemet, or the Black Land, was the Egyptian name for the country that stretched from the cataract falls at Aswan to the Mediterranean coast. The Egyptians farmed up to the desert edge, relying mostly on the silt of the Nile flood to fertilize the land. The Fayyūm, a natural depression watered by an offshoot of the river, attests to the earliest practice of agriculture in Egypt (ca. 5200 BCE). This rich land was subsequently exploited under the Ptolemaic pharaohs, who ruled after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander of Macedon in 332 BCE. Here, Greek and Egyptian mingled in life as in writing.

Kemet, or the Black Land, was the Egyptian name for the country that stretched from the cataract falls at Aswan to the Mediterranean coast. The Egyptians farmed up to the desert edge, relying mostly on the silt of the Nile flood to fertilize the land. The Fayyūm, a natural depression watered by an offshoot of the river, attests to the earliest practice of agriculture in Egypt (ca. 5200 BCE). This rich land was subsequently exploited under the Ptolemaic pharaohs, who ruled after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander of Macedon in 332 BCE. Here, Greek and Egyptian mingled in life as in writing.

The objects originating from Fayyūm towns like Tebtunis played a part in the day-to-day management of this multicultural society. A hierarchy of officials—from the smallest village to the royal court at Alexandria—assessed the country’s agricultural output. Since the days of the pyramid builders, Egypt’s governance relied on a bureaucracy that included temple landholders. Throughout this long history, priests were influential in the countryside. At Tebtunis, the main temple was dedicated to the crocodile god Soknebtunis. Educated priests managed land, maintained cult practices, and copied and studied texts within the sacred precinct.

At the same time as Christianity was gaining followers under the Roman empire, the traditional Egyptian religion faded. Churches built throughout the country often repurposed earlier religious structures, decorating them with multicolored scenes of Biblical passages and important church figures.

Current excavations at Tebtunis are run by a team from the Institut français d’archéologie orientale, Le Caire (https://www.ifao.egnet.net/archeologie/tebtynis/).

The Mistakes of Students

This school tablet was written on by several different people, meaning that it did not belong to an individual student. Instead, it may have been pass around by a teacher to practice handwriting. The teacher wrote the first line of each side and then instructed students to copy it. The text on the front states, “Begin: good hand, beautiful letters, and a straight line. And imitate it,” but this is disregarded by the students, who misspell or forget words. The students also reveal their inexperience in writing by repeating their own mistakes line to line rather than mirroring the model.

Wooden tablet with copied lines of instruction

Tebtunis Cemetery 8, Second to Third Century CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21416

Sounding it Out

In antiquity, far fewer people were literate and texts tended to be read aloud. For those who learned to write, exercises involved taking down spoken words on papyrus. Reading was thus intimately linked to writing. Students improved by copying out literary passages or moralizing maxims. Several pieces have been chosen to be read aloud

Homer’s Iliad is a classic school text of Graeco-Roman Egypt. The famous story of the fall of Troy has been discovered in numerous copies. Performers would also have offered dramatic recitations of epic poems like this.

Homer, The Iliad (Book 2, lines 507–518 and lines 531–556)

Tebtunis Town, T-547, Second Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 265

Greek read by Joshua Benjamins (Graduate student, University of California, Berkeley)

English read by David Wheeler (Graduate student, University of California, Berkeley)

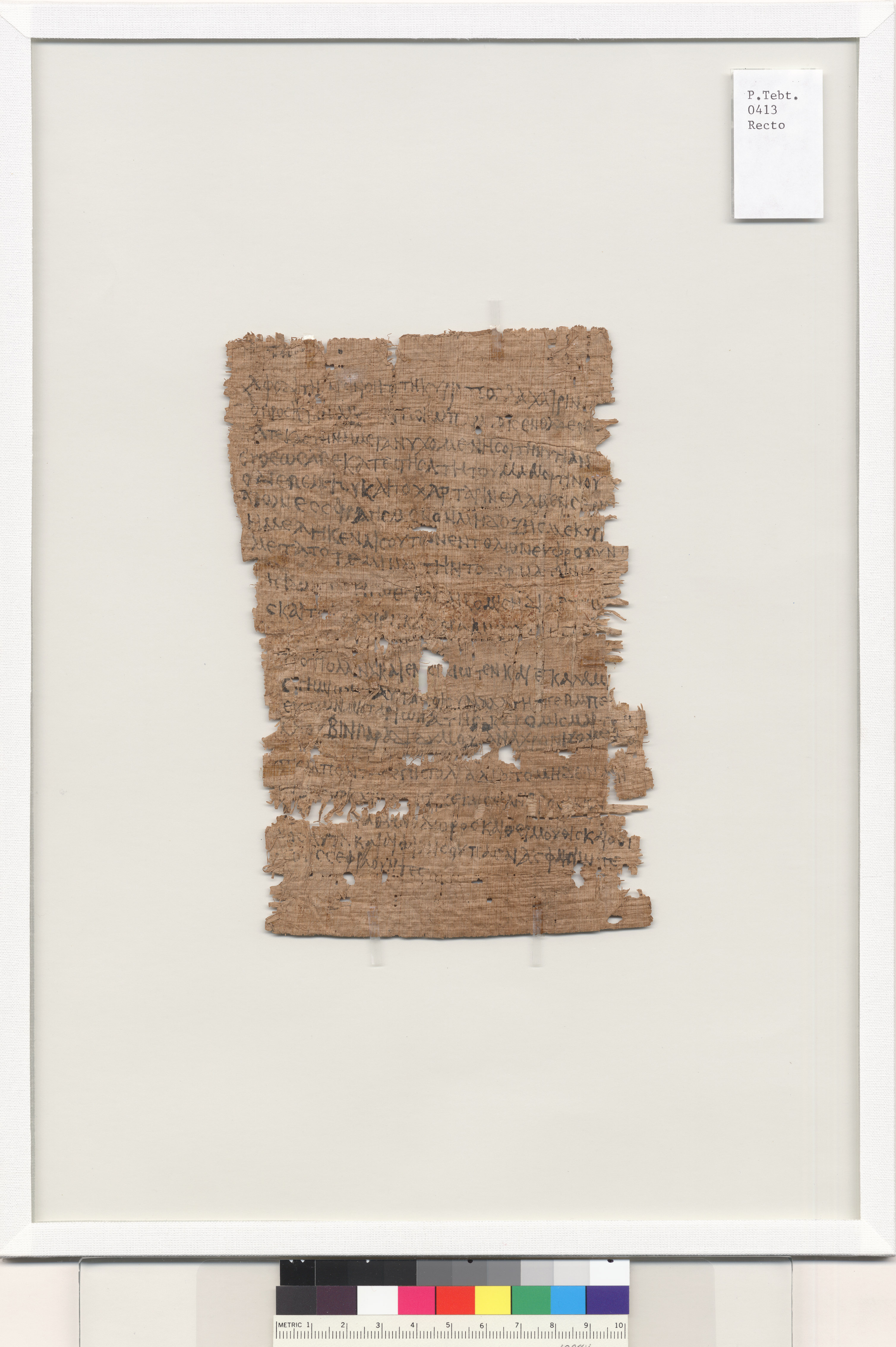

This text is a letter written by a woman to a woman. The labored handwriting and frequent mistakes suggest that Aphrodite herself wrote to her mistress. Letters too were often read aloud; in this way literate members of a household (or even a settlement) enabled others to learn the news that had been sent.

This text is a letter written by a woman to a woman. The labored handwriting and frequent mistakes suggest that Aphrodite herself wrote to her mistress. Letters too were often read aloud; in this way literate members of a household (or even a settlement) enabled others to learn the news that had been sent.

Letter of the Enslaved Aphrodite to her Mistress Arsinoe

Tebtunis Town, T-515, Second or Third Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 413

Greek and English read by Maria Mavroudi (Professor of History, University of California, Berkeley)

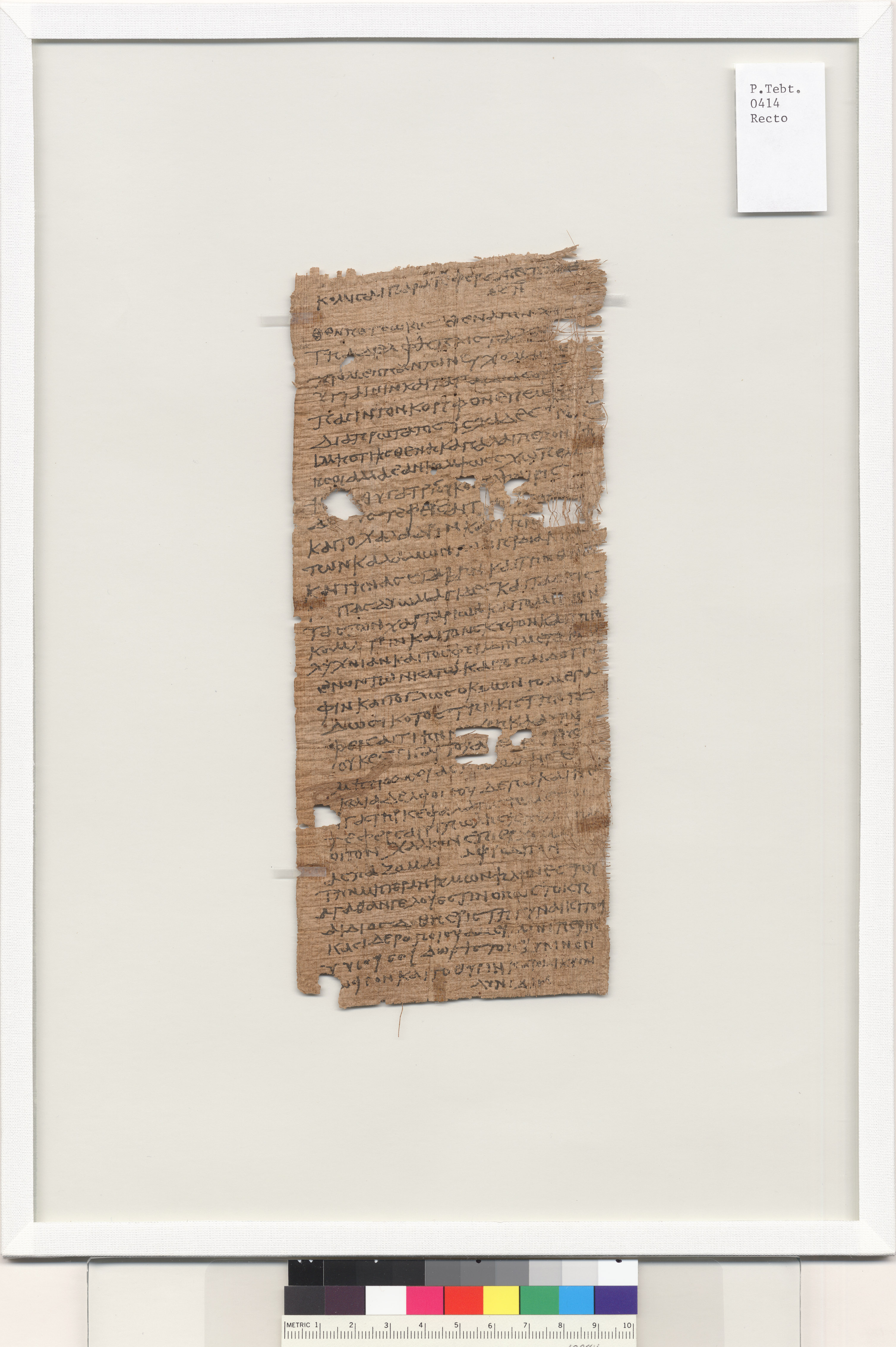

This text is a letter written by a woman to her sister. The phonetic writing and single hand suggest that Thenpetsokis herself wrote it. Letters too were often read aloud; in this way literate members of a household (or even a settlement) enabled others to learn the news that had been sent.

This text is a letter written by a woman to her sister. The phonetic writing and single hand suggest that Thenpetsokis herself wrote it. Letters too were often read aloud; in this way literate members of a household (or even a settlement) enabled others to learn the news that had been sent.

Letter of Thenpetsokis to her Sister Thenapunchis

Tebtunis Town, T-632, Second Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 414

Greek and English read by Maria Mavroudi (Professor of History, University of California, Berkeley)

Line drawing of a royal or divine woman sketched on the back of an administrative register

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Unknown Crocodile, Second Century BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt.frag. 14,291+14,292

Different Cultures, Similar Customs

Both of these painted statuettes were found at Tebtunis but are clearly examples of two distinct artistic styles. The bronze figurine of an Egyptian woman was possibly a depiction of the goddess Neith. Hieroglyphs were inscribed around the base, which would have been fitted into a stand. The Greek goddess Aphrodite is likely represented by the other figurine. The pose of the bodies, clothing choices, and writing reflect different cultural traditions. The worship of female deities, however, whether local or foreign, was a unifying feature of life in the multicultural town of Tebtunis.

Bronze Figurine of an Egyptian Queen or Goddess

Tebtunis, Ptolemaic or Roman Period (Third Century BCE to Third Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 5-173

Lead Aphrodite Figurine

Tebtunis, Ptolemaic or Roman Period (Third Century BCE to Third Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20508

Alabaster Statuette of Herakles

Nude figure of a male youth with a Greek inscription

Tebtunis, Ptolemaic or Roman Period (Third Century BCE to Third Century CE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20313a

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20313b

Colorful Gods on a Demotic Egyptian Account

A papyrus that has been reuse for a drawing of the Egyptian gods Tutu and Bes as well as a sacrificial bull

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Unknown Mummy, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt.frag. 13,385

Riding on Horseback

The rider on this stone stela wears the nemes headdress, traditional to Egyptian representations of gods and kings. But it is probably Heron, a Macedonian god who appears in Egypt during the Graeco-Roman period. The image of a king or god on horseback was associated with Alexander the Great. Iconographic similarities tie Heron to the Egyptian god Harpocrates, who was often represented slaying demons in the form of snakes or crocodiles. A legible Greek inscription dates the stela to year 25. Only Ptolemy X (89 BCE) and Augustus (5 BCE) reigned this long. The rest of the inscription, unfortunately partly erased, records the person who dedicated the stela: “… Manres alias Sisois, fuller.”

Limestone Stela likely Depicting the Macedonian Deity Heron

Tebtunis Town, 27 February 89 BCE or 10 February 5 BCE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20309

Photograph of Three Stone Objects Including the Stela of Heron

Churches and monasteries were built of mudbrick and reused architectural elements, decorated with multicolored scenes

Several Coptic Christian places of worship were built at Tebtunis after Christianity became the dominate religion in Egypt. The photographs and notes taken by Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt are all that remain of a tenth century CE church. A large tableau illustrated the Angel of the Abyss (Rev. 9:11) taking vengeance on sinners. Here a woman is having her soul removed from her body. Hunt copied out the inscription, labeled number 8, which reads: “The Decan devouring (?) the soul.”

Figure of a Decan (a Demon) Pulling the Soul out of the Mouth of a Woman

Arthur Hunt (1871–1934)

Tebtunis, 1899–1900

Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society, GR.NEG.085

Transcription of the Coptic Caption Written next to the Demon with a Later Translation in Red Ink by the Coptologist Walter Crum (1865–1944)

Arthur Hunt (1871–1934)

Tebtunis, 1899–1900

Courtesy of the Griffith Institute Archive, University of Oxford, Crum MSS 24.67, pg. 11

Decorated Church Apse at Tebtunis

Image of a tenth century CE church with elaborate multicolored scenes. The apse was decorated with a depiction of Christ and the symbols of the evangelists (derived from Ez. 1:10) above saints of the Coptic church: Athanasius, Anthony, and Pachomius.

Arthur Hunt (1871–1934)

Tebtunis, 1899–1900

Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society, GR.NEG.083

“[T]hey are angels who have come for him…”

The Coptic monk Shenoute (332–451 or 350–466 CE) was born north of Thebes and founded a community centered around the White Monastery at Sohag. George Reisner excavated at Naga ed-Deir, just south of Sohag, and discovered this text in 1904. Reisner worked mainly in ancient Egyptian tombs, many of which were repurposed by Coptic Christians to live or worship in. This fragment of parchment (stretched and treated animal hide) is a page from a codex, or bound volume, which includes a sermon by Shenoute that outlines the nature of the judgement after death. The book was clearly used, as a second reader added notes, the smaller letters seen midway down the right side of the text.

Shenoute of Atripe, On the Judgement

Naga ed-Deir, Ninth Century CE?

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Hearst 1281

Recto and verso

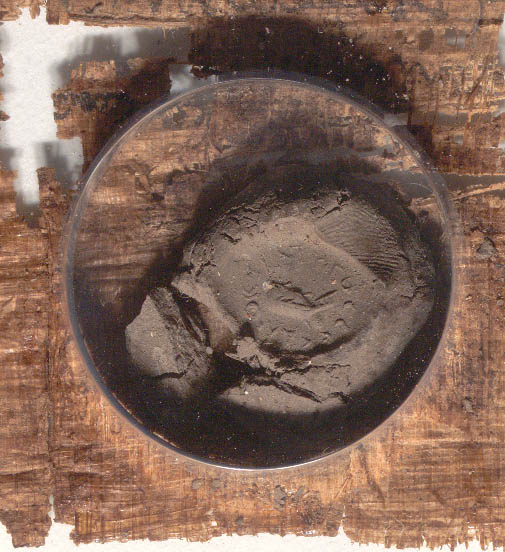

Sealing Documents

A common way that ancient scribes validated or secured a document was to attach a sealing to it. Seals carved into stone or made out of ceramic could combine text and image; many were worn as rings. A seal was pressed into soft clay, which was fixed onto the papyrus. When a woman named Semele wanted justice, she turned to the governor of the Fayyūm (stratēgos). He ordered the accused, a husband and wife from Tebtunis, to appear before him by sending this warrant with his official seal, which reads, “The stratēgos summons you.” Sealings on the opposite side of this text suggest that it kept the folded papyrus fastened. Sealings were often broken when they were opened by their intended recipient.

A warrant with a clay sealing from Tebtunis

A warrant with a clay sealing from Tebtunis

Tebtunis Town, First Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt II 290

Papyrus with a clay sealing

Papyrus with a clay sealing

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Unknown Crocodile, July or August 5 BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. UC 2446

How to Store Papyrus

Important documents were often preserved by storing them together in a jar. These two documents were found together. This first papyrus lists nine individuals who owe money to a man, Tyrannus, and the second discharges a debt owed to the father of a woman, Tyrannis

List of Debtors

Tebtunis Town, T-704, Before 198 CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 639

Settlement of a Debt

Tebtunis Town, T-703, 23 February 198 CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 397

Ceramic Bottle with Polychrome Decoration

Tebtunis Town, First to Fourth Century CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley 6-20226

Menches, the Village Scribe

An Egyptian scribe named Menches, also known by his Greek name Asklepiades, worked at the village of Kerkosiris near Tebtunis in the Fayyūm from before119 until the end of his appointment in 110 BCE. He was responsible for surveying agricultural land, receiving petitions from his fellow villagers, and communicating with the capital in Alexandria. As papyrus was too valuable to waste, some of his documents were reused for other texts. Around 91 BCE, his objects and others made their way to the embalmers at Tebtunis. The papers were wrapped around the dried-out bodies of sacred crocodiles as cartonnage (similar to papier-mâché) or stuffed inside them. In the winter of 1900, Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt excavated crocodile mummies at Tebtunis, bringing the activities of Menches back to light two thousand years later.

Censure of Village Officials for Poor Revenue Management

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Crocodile 27.31, 27 February and 2 March 113 BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. I 27

Letter of Complaint about Village Scribes

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Crocodile 17.3, After 22 May 117 BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. I 24

Account of Expenditures by the Office of Menches to Conduct an Agricultural Survey

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Crocodile 28.14, 22 February to 24 March 112 BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. I 112

Spending Money in the Fayyūm

Coinage, as an alternative to payment in kind, were introduced to Egypt prior to the conquest of Alexander but became an essential aspect of the economy under the Ptolemaic kings. Silver, bronze, and gold coins were produced in Alexandria and at a number of different mints in the countryside. Symbolism on coins was important. Some kings chose to honor and associate with past rulers or important gods in Egypt.

Silver Tetradrachm of Ptolemy X Found in a Hoard of Ptolemaic Coins

Tebtunis Temple, 92/93 BCE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-22342

Eagle and image of Ptolemy I

Silver Tetradrachm of Nero

Tebtunis, 66/67 CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-22617

Images of Nero and Augustus

Silver Tetradrachm of Hadrian

Tebtunis, 121/122 CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-22666

Images of Hadrian and Isis

Bronze Coin of Antoninus Pius

Tebtunis, ca. August 138 CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-22724

Images of Antoninus Pius and Serapis

Collecting Taxes

Palm frond of a Roman gradus (74.4 cm) with marks dividing it into six unciae (12.4 cm)

Tebtunis, First to Fourth Century CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20549

Receipt, written on an ostrakon, for the beer-tax paid by Pharion

Tebtunis, First Century CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, O.Tebt. 1

A list of the priests of the crocodile god Soknebtunis, who are exempt from various taxes, and the revenues of the temple

Tebtunis Town, T-140, After 29 July 108 CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. II 298

A Temple Fit for a Crocodile God

A single fragment from the temple of Soknebtunis, the main crocodile god of Tebtunis, was removed by Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt during their excavations. This limestone block would have been fully painted with bright multicolored figures set against a white background. Although the gods’ names are not carved next to them, it has been suggested that from left to right, the relief depicts the god Sobek in his form of Lord of the Wadj-plants, the goddess Nut with a pot headdress, and, as part of a separate scene, a pharaoh wearing the atef-crown.

Fragment of painted relief from the temple of Soknebtunis

Tebtunis Temple, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-20301

Temple Relief Depicting Soknebtunis on his Throne

Gibert Bagnani (1900–1985)

Tebtunis, Early 1930s

Courtesy of the Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario. Gilbert and Stewart Bagnani fonds. Gift of Stewart Bagnani, 1991

The Processional Route at Tebtunis Flanked by Lion Statues

Gibert Bagnani (1900–1985)

Tebtunis, Early 1930s

Courtesy of the Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario. Gilbert and Stewart Bagnani fonds. Gift of Stewart Bagnani, 1991

Painted wooden panel with captioned image of a priest and god

Tebtunis Cemetery 7 or 8, First to Third Century CE

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, 6-21387

Letters about the Fayyūm Crocodiles

A letter is forwarded to the official Horos in advance of the visit of a Roman senator to the Fayyūm. In anticipation of his arrival, the officials are urged to prepare everything carefully, including the crocodiles. Ancient travel guides include stories about how the animals are kept and given food by eager tourists to the region.

In this nome [=Fayyūm] they worship the crocodile greatly, and there is a sacred one there that is tended by itself in a lake, and is tame to the priests. It is called Souchos, and is fed on grain, meat, and wine, which are always being fed to it by the foreigners who there to see it.

Strabo, Geogr. XVII, 1, 37–38

Translated by Duane W. Roller

Lucius Memmius, a Roman senator, tours the sites and feeds the crocodiles

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Crocodile 17.7, After 5 March 112 BCE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. I 33

Greek read by Joshua Benjamins (Graduate student, University of California, Berkeley)

English read by David Wheeler (Graduate student, University of California, Berkeley)

Certain individuals at Tebtunis were responsible for the sacred animals, namely the crocodiles dedicated to the god Soknebtunis. These “crocodile keepers” (saurētai, from the root saura, lizard, also found in the word dinosaur) fed the crocodiles and bred baby crocodiles to supply the temple. They were active participants in the Fayyūm economy as this letter illustrates. In relation to a loan of wheat, the crocodile keepers offered a security payment. Something went wrong, however, leading Petenephiës, the author of this letter, to ask that the security be returned so that they might pay for crocodile food!

Letter authorizing the release of the crocodile keepers’ security

Tebtunis, Cartonnage from Crocodile 17.8, 29 July 114 CE

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, University of California, Berkeley, P.Tebt. I 57

Greek and English read by Leon Petrakis